The 3 Key Ideas from Aristotle That Will Help You Flourish

A quick primer on flourishing, virtue, and becoming who we are through practice

What does it mean to be happy and to live a good life? How do we focus on what matters and live up to our own potential? Why do some people succeed while others merely get by?

These simple and essential questions have been with us for millennia and most of us find ourselves wondering about them as we mature. If you've wondered about them, you're in good company with a long line of philosophers, spiritual teachers, and religious leaders.

One of the most thorough and compelling discussions of those questions was posed by Aristotle over 2300 years ago. Given that these questions focus on our conduct, they are ethical questions. I'm going to do my best to share the brilliance of his thinking in something that can be read in 10 minutes.

Aristotelian Ethics ... in 10 Minutes

To get the basics of Aristotelian ethics, you have to understand three basic things: what Eudaimonia is, what Virtue is, and That We Become Better Persons Through Practice.

1. Everyone Seeks Eudaimonia (Flourishing)

Eudaimonia is Greek and translates literally to "having good demons." Many authors translate it as "happiness," but I don't think that's the best translation or way to understand it. "Well-being" and "flourishing" are closer to what Aristotle means, and I think that of the two, "flourishing" captures the full range of the way he uses the word. And someone who is flourishing is living The Good Life.

According to Aristotle, all humans seek to flourish. It's the proper and desired end of all of our actions. Flourishing, however, is a functional definition. And to understand something's function, you have to understand its nature. Keep in mind that Aristotle, unlike Plato, was an empiricist — that is, he was trying to describe what he was seeing, rather than stating what he thought it should be.

In Aristotle’s schema, there are four aspects of human nature, and he is often quoted as saying "Man is a political creature." Aristotle's meaning is much richer than the way it's translated, though, because he means that "man is a rational creature who lives in poleis (societies)." ("Poleis" is the plural of "polis," from which we get the root "poli" that's used in so many words like polite, political, police, etc. that have to do with how we interact in groups.)

How do we get four different aspects out of "rational creature who lives in societies?" Two are determined by the type of thing we are — that is, we are animals. So it looks like this:

We are physical beings (because we are animals). As physical beings, we require nourishment, exercise, rest, and all the other things that it takes to keep our bodies functioning properly.

We are emotional beings (because we are animals). What separates animals from plants, according to Aristotle, is that animals have wants, desires, urges, and reactions. We perceive something in the world that we want and we have the power of volition to get it; likewise, we have the power to avoid the things we don't want. For humans, these wants can get pretty complex, but at rock bottom, we all have (emotional) needs and wants that spring from rather basic sources.

We are social beings (because humans live in groups). We must live and function in particular societies. "No man is an island," and we are the type of being that does well only in social settings. Our social nature stacks on top of our emotional nature, such that we have wants and needs that we would not have were we not social creatures. For example, if we were the type of creature that flourished as hermits, the need for trust and friendly cooperation would not be nearly so pressing.

We are rational beings. To the Greeks — and, let's be honest, most cultures, including our own contemporary one — what made humans human was our rationality. We are creative, expressive, knowledge-seeking, and able to obey reason. We might not always obey reason and we may sometimes not want to exercise our minds, but a large part of our existence relates to our being rational animals.

You can see Aristotle's taxonomical approach in play. He's not working backward from some ideal version of humanity, but rather looking at the specific things that make us the specific kind of being we are. It's this same approach that is the bedrock of Western science, and it's so ingrained in the way we think about the world that it would be easy to miss how brilliant and innovative his approach was, even if his answers to scientific queries are more wrong than right. The irony here is that he founded a way of thinking that ultimately gave us tools to show that many of his final conclusions were wrong.

Flourishing Is a Holistic Concept You can't truly flourish if you're not flourishing in one of the four aspects of human nature. This principle plays out in our everyday lives when we see people who are so emotionally stunted that they can't function well in society... or who are so obese that they can't enjoy life... or who are so socially inept that they can't fit into the type of society that would develop their intelligence. The list goes on and on.

The different aspects of our natures are tiered in the way that they are presented above so that the physical is below the social, which is below the rational. This may sound familiar to those of you who are familiar with Maslow's Hierarchy because it's in effect the same thing. But 2500 years elapsed before Maslow verified what Aristotle had said all along.

With an understanding of flourishing in hand, discussing virtue becomes easy.

2. On Virtue

What Is a Virtue? A virtue is a trait of character that enables a person to flourish.

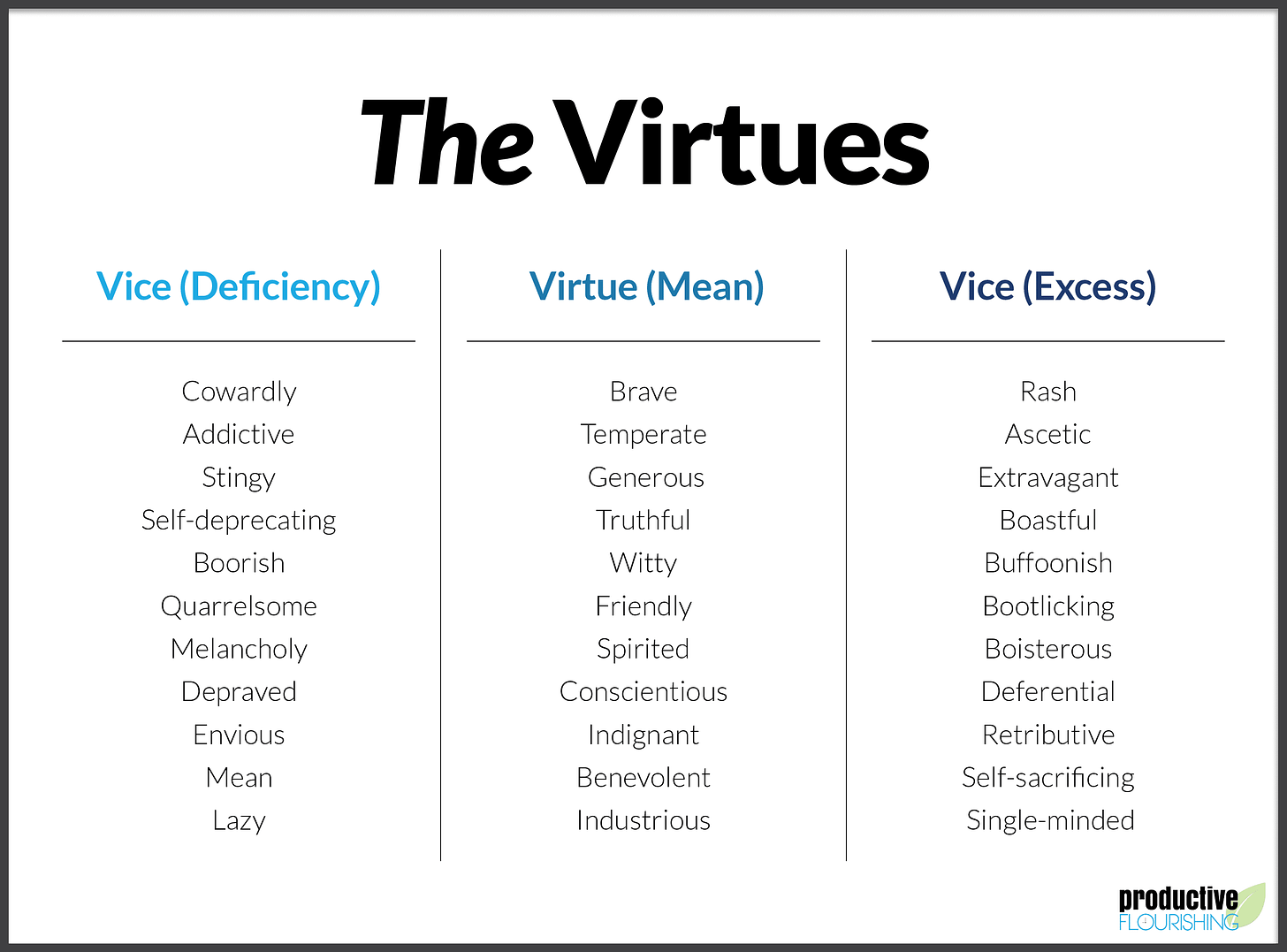

The Doctrine of the Mean This is a key phrase to understand Aristotle. Consider the virtue of bravery, for example. An excess of bravery leads people to do really stupid things; the example I normally use is the frat-brat who'll jump off the fraternity house roof just to prove how brave he is. It's not brave; it's rash. On the other hand, people who have a deficiency of bravery are cowards; they won't put their ass on the line for anything. The virtue of bravery lies somewhere in between the deficiency of bravery (cowardliness) and the excess of bravery (rashness).

So it is with all of the different virtues: the virtuous trait is that which is between the deficiency of that trait and the excess of that trait.

What Are the Specific Virtues?

I'll not discuss all of the virtues, but some are worth a quick discussion:

Temperance - This one has to do with calming one's bodily passions and desires. Always acting on your physical passions and desires will not lead to flourishing. However, always denying your physical passions and desires is also denying a component of your nature and will also not lead to flourishing.

Wittiness - Many people don't think this should be on the list, but when you think about it, it makes perfect sense. People naturally want to be around people who are funny and who lighten the mood. We tend to avoid grumps, and buffoons, though initially fun, grow tiresome after a while. So, having the virtue of wittiness enables us to flourish in the social aspect of our lives. The analysis of friendliness is much the same.

Spiritedness - The insight here is that you should be passionate about things in the right circumstances. There are situations where anger is the appropriate, virtuous response, and if you're never able to become angry, you're deficient in spirit, and if you're always angry, you've got an excess of anger. This trait is the emotional analog of temperance.

Indignant - Aristotle discusses indignity as a virtue in the sense that he thinks we should be upset if people do well undeservedly. For example, if someone wins because she cheated, the proper, virtuous response is to be upset or angry. On the other hand, some people are so envious that they are angry when anyone does well, and some people are so spiteful that they delight in other people's misfortunes. The proper, virtuous trait is to be delighted when other people do well because they deserve it.

Benevolence - How can one have benevolence in excess? Isn't it always a good thing? Nope. If we get an excess of benevolence, we can't see that sometimes to do the right thing, you can't help someone. Do you know drama queens who always call to talk to you when they're going through their crises? The proper response is to, at a certain point, recognize that you can't help them (in reality they don't want it) and walk away. However, never helping anyone is a defect and should be avoided as well. (Some people confuse benevolence with generosity. That one has to do with how you handle your resources.)

How Are All of the Virtues Related? What links all of the virtues is phronesis, a Greek word best translated as "practical wisdom." It's not quite intelligence, although it is a rational trait; it's more like knowing what the mean is in the particular circumstance you're in. How does one know what to do in a particular circumstance?

3. We Become More Virtuous Through Education and Habit

If we're lucky, we're brought up in an environment where the adults around us teach us how to be virtuous. There are two ways that they can do this.

The first way is just by training us to have habits that enable us to flourish. For example, they may instill in us the tendency to exercise or to play sports. They may also instill in us the habit of sharing, being friendly, being brave, and all the other virtues. In other words, they make it part of our innate character; they are training us how to be.

The second way normally follows the first. After we reach a certain age of maturity, they can start to teach us why it's good to have the habits that they've been inculcating. Children don't understand flourishing, but adolescents and adults can. Adults are honing our practical wisdom at this stage, since they are teaching us in what circumstances we ought to do certain actions. They are in effect teaching us why we ought to be the type of person we are.

Of course, the best way for them to teach us to be virtuous is to exhibit virtue in their characters. If we ever wonder what we should do in a certain situation, then finding the answer is as easy as finding a virtuous person and asking her what she would do. And how do we know who a virtuous person is? We just look for someone who's flourishing.

At a certain point, though, we become responsible for our own characters. It is at that point that we begin to actively and intentionally hone our characters. We continue to improve our physical body, our emotional state, our ability to live with others, and our minds. We continue to reinforce good habits, acquire more knowledge, help those around us, and find peace within ourselves.

We have the knowledge, we have the habits, and we have the understanding that the good life is up to us. The end state: we flourish.

Another philosophical giant, Immanuel Kant, approaches questions of ethics from completely different starting points. Read about the mere means principle to see how Kant's theory contrasts with Aristotle's.

We are not animals, the quality that we can add to our virtue is evidence for that