(This post is a slightly edited excerpt from Chapter 9 of Team Habits.)

If a $500 office printer breaks, we have to fill out a form or purchase order to replace it. That $500 gets scrutinized before it’s approved (or not).

But when we want to call a meeting? Nothing stops us, even though most meetings cost far more than $500 from the perspective of salaries and blocks of time.

In business, it’s harder to get approved to use large funds than it is to utilize the thing we have a massive shortage of: people’s full engagement and attention.

Let’s look at the true cost of a meeting. If you take nothing else from this post, hard-freeze this into your brain and your team’s logic:

A one-hour team meeting is NEVER just one hour’s worth of time. It’s at least one hour of each teammate’s time.

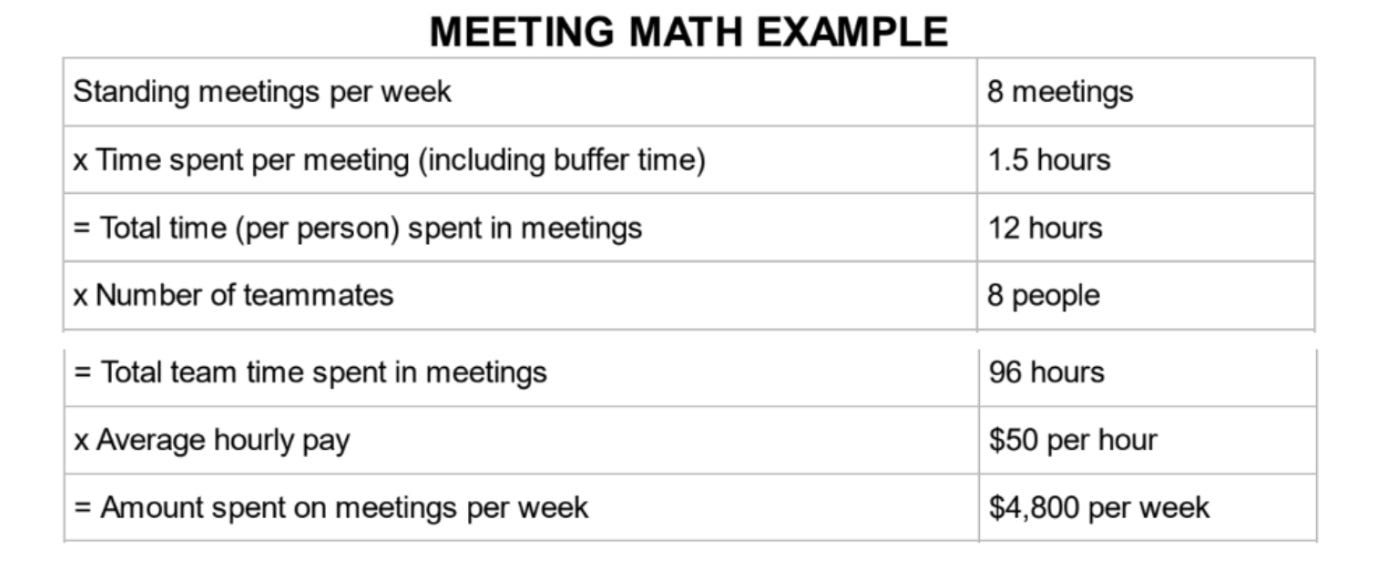

Let’s take a look at the real meeting math:

How Long Are Meetings, Actually?

You’ve called a one-hour meeting. How much time does that really soak up?

Before the meeting: fifteen minutes of prep and transition. This is the time spent transitioning from whatever you were doing into meeting mode.

Meeting time: the one hour of time actually scheduled for the meeting.

After the meeting: fifteen to twenty minutes of exit and admin time. (Most meetings create more work, whether that is sending out a message, spending time making a decision about what was discussed, or just transitioning back into deeper work.)

When you look at it this way, a one-hour meeting really takes up at least ninety minutes of a single teammate’s time.

How Many Meetings Do You Actually Have Per Week?

You may look at your calendar and say you have between three and five standing meetings every week. Not bad, right?

Until you factor in all the unexpected “crutch meetings” that pop up at the last minute. (Crutch meetings are meetings that act as a stand-in for a poor team habit; we’ll talk about them in more detail in a future post.)

Normally when I do this exercise with clients, they’ll tell me that 50 percent of the meetings they had last week were one-off meetings that don’t normally happen.

But when we go further back through their schedules, it becomes clear that “one-off” meetings end up taking up the same amount of time each week. They might as well be considered standing meetings, which means you need to take them into account in your schedule. (And then, as we’ll discuss, figure out how to eliminate them.)

Taking crutch meetings into account, you may actually have eight standing meetings a week that average forty-five minutes each. Using the rule of thumb that there will be at least thirty minutes of prep and admin time before and after each meeting, that’s a full ten hours of every workweek eaten up by meetings.

That leaves you thirty hours in a typical workweek to do the work you’re ostensibly being paid to do. Not too bad, right?

Hold on just one second — it gets worse.

When Are Meetings Held?

When the meeting is held is just as important as how long it is. If you schedule a meeting at 8 a.m., for example, you catch most people in their warm-up cycle. Most people aren’t ready for deep conversation at that time, which means the meeting will be longer than needed, more confusing than anticipated, or just plain useless.

What’s more likely is that you put invisible work on your team to show up earlier to work to prepare for the meeting. Time spent preparing for the 8 a.m. meeting displaces the time your teammates were probably spending on self-care, family, or sleep.

Scheduling meetings at 9:30 or 10 a.m. isn’t much better but for different reasons. That mid-morning meeting essentially ensures that your teammates don’t get a full focus block on either side of the meeting. Unless they get to work super early, they will probably spend the morning on admin and then spend the hour after the meeting pushing things around before lunch. That hour-long meeting ends up demolishing an entire morning’s worth of focused work.

At Productive Flourishing, we tend to schedule meetings at 11 a.m., 1 p.m., or 3 p.m.

An 11 a.m. meeting gives people a good focus block of work in the morning, after which they can come to the meeting warmed up and ready.

A 1 p.m. meeting harnesses that “just back from lunch” energy while leaving a solid amount of time in the afternoon for focus blocks,

3 p.m. meetings are something we use with caution. They can be great at getting something near-done out the door or setting up the next day, but they can also be incredibly ineffective because we’re catching so many of our teammates in the least energetic part of the day given their chronotypes and time zones.

This can be more difficult to manage with teams that span multiple time zones. The important thing is to work with your teammates to find the option that best fits all of your schedules.

The day on which meetings happen during the week can also be a force multiplier or diminisher because it determines the shape and cadence of the week. This is why we see so many planning and coordination meetings on Monday or Tuesday. If you schedule a planning meeting on Thursday, people are either frazzled or distracted by looming end-of-week deadlines. Whatever you planned during that meeting will be tough to remember by the following week.

It’s less palpable, but the timing of certain types of meetings during a month can also shape the workflow of a month or quarter.

In our imaginary meeting math example, we’ve established that you technically have eight seventy-five-minute meetings throughout the week. Take a look at when they fall. How many of them are effectively torpedoing an entire morning’s or afternoon’s worth of work?

How Many People Are at the Meeting?

The final calculation in meeting math is this: If you have one hour-long meeting with eight people, you’re actually having twelve hours’ worth of meetings. (This is after we take into account the buffer time on either side of the meeting.)

You’re using up twelve hours of time and attention. Twelve hours of people’s salary. When you think about it that way, eliminating one meeting can eliminate that claim on eight people’s attention and free up much more time for actual work to happen.

Meeting math is part of the answer to the question of why your team is having such a hard time pushing projects forward. Why are they not getting strategic work done? Why are they burning out? Why do they keep getting blocked by strategic-recurring-urgent work logjams?1

Once you factor in meeting math, you can see why there’s just not enough time in most people’s calendars to do their work.

If they are getting work done, odds are that they’re doing it in such a way that it is pushing them along the road to burnout because the only times they can find focus blocks are nights and weekends, when their schedule isn’t being interrupted by meetings.

The team in the above example is spending $240,000 per year on meetings, yet no one can get approval to replace the printer that’s been out of date for years.

$500 requires approval and a requisition form. $240,000 is “free.”

I’m not trying to say that all meetings are bad.

I am saying that I want your team to have meetings that intentionally and habitually act as a multiplying force of your team’s ability to do their best work. Understanding meeting math can give you a powerful tool and language to start tackling team habits around meetings.

Rocket Practice

As I say in the book, none of the above is rocket science. It’s not hard to understand and the math is easy.

The difficulty is in actually using the insights to build team habits.

And, let’s get real here, it’s easy to see when someone else’s meeting may be unnecessary at the same time that we think our “it’ll just take an hour” meeting is critical and the fastest way to get through something.

That’s the thing about bad team habits. They’re not behaviors that other people do to us; they’re also behaviors that we do to other people.

If you want to do real meeting math and see how much of your time is being spent in or around meetings, here are some questions to ask yourself and run through with your team:

Look at your schedule of standing meetings on a weekly and monthly basis and then work through the meeting math above. To your best estimate, how much time and salary are being spent on meetings each week?

When do meetings happen during the day? Do they impede potential focus blocks for your teammates? Is there a different time of day that would make more sense to ensure that everyone in attendance can engage? Be sure to account for teammates in different time zones.

Does your weekly, monthly, and quarterly meeting schedule drive work forward and create force multiplication? Or does it diminish and squander the team’s time, energy, and attention?

It’s worth repeating: A one-hour team meeting is NEVER just one hour’s worth of time. It’s at least one hour of each teammate’s time.

Is your team's meeting math not mathing?

Our Team Meeting Makeover workshop directly addresses meeting fatigue, time sinks, and helps you create gatherings that drive meaningful outcomes instead of draining productivity. Reclaim those hours and transform meetings into strategic assets that strengthen belonging while freeing up time for deeper work.

Explore our team workshops or other ways we can support your team.