How to Set SMART Goals

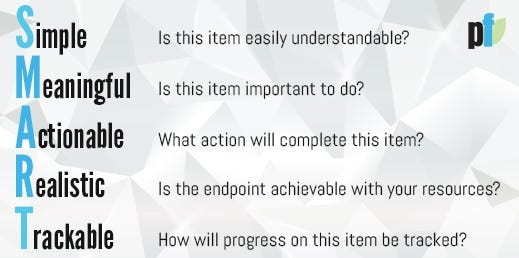

Making your goals Simple, Meaningful, Actionable, Realistic, and Trackable

Take a quick look at some of the goals you've made for yourself. A goal could be as broad as your bucket list or as narrow as your daily To-Do list. Are you setting yourself up for success with smart goals? One of the things that trips many of us up is that the way we're writing our lists and plans isn't as effective as it could be. I've written a good bit about writing effective To-Do lists, but today I'd like to share the SMART framework that I use and help others implement.

Being stuck with an idea that’s not yet a goal keeps you swimming in the ocean of possibility, which is fun for a little while but exhausting over the long term. Converting that idea into a goal gives you a safe shore to swim to.

Before I begin, though, I want to be clear that this framework floats around all over the place and different SMART-goal advocates attach different meanings to each letter. The way I use it is focused on creative types — though our challenges aren't that unique, the way we approach our work often is. So, even if you've seen another discussion of making SMART goals, there might be something here to think about. SMART is an acronym that helps you evaluate whether your goals or action items have enough information in them to actually be useful. Here's the framework I use:

Thinking about your goals using this framework has two major benefits: 1) it ensures that you're thinking in a considered way about the commitments you're making to yourself, and 2) it helps you express your goals in a way that makes it more likely that you'll complete them. I'll discuss each component in turn.

Is Your Goal Simple?

A SMART goal is simple when you can look at it without wondering. You shouldn’t have to look up something else to understand its meaning.

Simple doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s easy, but simply stated goals help you look at a list and know exactly what you need to do. If you look at a goal and have to think about what you need to do to count that goal as done, your goal isn’t simple.

When we set a complicated goal for the future, it may be difficult to hold on to its meaning over time. A complicated goal made when we’re in the zone may be harder to understand when we’re not — the last thing we want to do first thing in the morning is struggle to figure out what we’re supposed to be doing, and knowing that we’re retreading ground we’ve already trod makes it more frustrating. Simple goals help set us up for success.

As we’ll see in a moment, simple and actionable are often related: actionable goals tend to be simple. That said, it’s entirely possible and normal to have a goal that’s simple but not actionable, or a goal that’s actionable but not simple.

Is Your Goal Meaningful?

A SMART goal is meaningful when you can look at it and quickly understand the importance of completing that goal.

What often trips people up is that they equate meaning and desire, but that’s an unnecessary relationship: you might not want to do something that’s meaningful, yet it still might be meaningful to do. For instance, you may not want to do your taxes, do the back-to-school shopping for the kids, or help transition your aging parent to assisted living, but these projects have meaning in the broader context of your life.

Is Your Goal Actionable?

A SMART goal is actionable when it’s immediately clear what action needs to be taken to accomplish the goal.

If there’s nothing you can do to bring about your goal, it’s not a goal — it’s a wish. A wish is granted by someone or something other than you and is thus out of your control. You can’t plan for it or work toward it by clearing space on your calendar. I’m all for wish lists; combining wish lists and action lists, not so much.

Making a goal actionable is perhaps the simplest criterion to meet because it’s just a matter of thinking of the actions that will bring about that goal. The simplest way to make a goal actionable is to begin the phrase with a verb. Instead of “Chapter 1,” phrase the goal as “Write Chapter 1.”

Is Your Goal Realistic?

A SMART goal is realistic when the endpoint is achievable with the resources you have available.

We creative folks have a lot of friction with this one, as we have that peculiar ability to change the world in important ways. To be creative is often to see parts of reality as tentative.

However, just because we can change the way things are doesn’t mean we can do it all at once or do so without regard to the basic constraints of reality. Try as you might, you can’t change the fact that it takes time to do things well or that you need sleep. You also can’t change social reality overnight — or, if you do, it will probably be accidental.

Rather than put your head in the sand and try to deny the way things are, asking whether your goals are realistic helps you figure out ways to make it more likely that you’ll succeed. Identifying drag points — those places and elements where your goal is likely to go sideways — allows you to plan ways to overcome them. Better to beat the dragon you already know is there than pretend as if it’s not there and then be surprised by it.

Realistic goals and trackable goals are often heavily interrelated, especially when the way you track your goals is based on time. An unrealistic goal can often be made realistic and doable by changing your expectation of how long you think it would and should take.

Is Your Goal Trackable?

A SMART goal is trackable, quantitatively or qualitatively, when it’s clear what progress means.

Most SMART-goal advocates use the “T” for time-specific, but I prefer to leave it more open. Some goals don’t fit into a temporal framework as easily as others, but it doesn’t mean that we can’t actively do things to bring about those goals.

Consider the broad goal of being a better friend. Setting a goal to become a better friend by June 1st is neither meaningful nor simple. However, it can be a recurring broad goal that you can check in about every once in a while by asking yourself what you’re doing to be a better friend to specific people. Understanding a goals in this way makes plenty of room other kinds of uniquely human activities such as contemplation, intuition, mindfulness, and unstructured learning in ways that setting rigid time frames can unhelpfully constrain.

Most goals are best formulated with time specificity: assigning a time line to a goal can help us identify the simple actions we can take to bring about that goal at the same time that it makes the goal feel more real.

Keep Things at the Appropriate Level of Perspective

Throughout this post, I've used goals at different levels of perspective to illustrate that items at different levels might have different presentations. Though this is obvious, many people start wheel-spinning precisely because they've made a list that has items at different levels of perspective and it's blurring the clarity they might otherwise have.

Take a daily To-Do list, for instance. On such a list, you don't necessarily have to have a time specified for each item if every item needs to be done today — it's implied from its being a daily To-Do list. However, what many people do is place a bunch of items that don't need to be done today on that list, and because it's not clear what's what, every time they look at the list, they have to evaluate whether that thing actually needs to be done today.

Even worse is when they put projects on a daily task list, because then they're trying to evaluate each related task of that project at the same time that they're scanning the rest of the list. That's a lot of mental gears turning just to see what you need to be doing right now.

If you've ever wondered why I have a place for Projects and Tasks on the planners, now you know why. By separating the different levels of perspective, you can have some clarity for each one, as well as having some idea of why those tasks are important; in that sense, the SMART framework is baked right into the design of the planners.

I mention lists and levels of perspective here because many of us look at goals in the context of plans and lists rather than one at a time, or in other cases, as soon as we start thinking about a given goal, we start thinking about the lower-level actions required to complete it or the higher-level domains that give that particular goal a context. So, for many of us, asking whether our goals are SMART is effectively asking us whether our lists are SMART, too.

The next time you're planning, ask yourself two questions:

Are these goals or action items SMART?

Would this process be easier if the items were split out and grouped according to the appropriate level of perspective required to process them?

To learn how to measure the success of your SMART goals, dive into Chapter 4 of Start Finishing. We cover this, and how to choose the people to surround you as you move towards your goal.

"temporal framework" I love that phrasing.